Corporalità 2004

Idea/Choreography/Dance: Yvonne Pouget

Stage direction: Martina Veh

Counter-Tenor/Acting/Dance: Christopher Robson

Dance: Thierry Paré

Musikalische Leitung: Christoph Hammer

Lightning Design: Arndt Rössler

Word premiere: 29.01.2004 at Museum Für Abgüsse Klassischer Bildwerke, Munich, Germany; took part at the Europäischen Kirchenmusikfestival at Schwäbisch Gmünd, Germany, 31.08. 2008 with the musical direction of Axel Wolf ant the United Continuo Ensemble.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

About the Play:

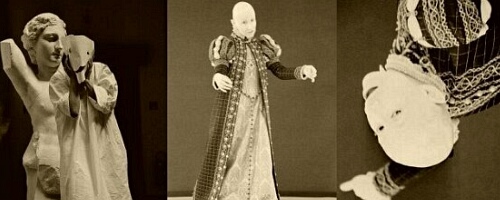

The cultivation of Body, Spirit and Soul is highlighted in „Corporalità“ via the fascinating combination of baroque music with the expressive possibilities of Butoh. Butoh Dance, which came to Europe from Japan after the Second World War, is developed from traditional Japanese dance combined with modern elements. Central to Butoh Dance is the element of the Body combined with the personal Life-experience of the dancer. Butoh has its roots in the Noh and Kabuki theatre traditions, as does much of the German Expressionist dance movement today. In Butoh dance, beside the typically salient white painted body of the dancer, the strongest contrasts are characteristic in the movement: fast-slow, soft-hard, or wild-tender.

The early Baroque musical world of Monteverdi’s impressive and emotionally deeply expressive monologue “Lasciate mi morire“ (better known as the Lamento d’Arianna) from his lost opera “ARIANNA“ of 1608 forms the musical basis or pivot of the production.

The Desire for Life (Lebenslust) and the Joy of Existence (carpe diem) are inseparably connected with the skills of the “other side” and the cult of the transitory (memento mori). Joy and beauty do not have existence. In the Baroque, death is pervasive and always overshadowing the existing “Weltlust” with its finiteness. Thus is mortality and earthliness in the project of greater interest – here celebrated in the dance.

The dance is an intimate inter-psychological process with the audience, equally volatile and transient.

Music dance theatre “Corporalità”, in the Johanniskirche

“Extraordinarily commanding physical control and body language”

Rems Zeitung, Remstal, Schwäbisch Gmünd, 05.08.08.

“Music goes without dance and dance also without music Yet both belong together, like the egg and the chicken, because dance is rhythm, and rhythm is music.

Dance is movement and music so often rules over movement: often a problem of our so clearly regulated concert culture. Everyone goes thus without the other one, so much is clear, but what is one without the other? How would the Concerto or Symphony without movement have worked, or the Aria without movement, the expression of the singer?

Thus a fourth factor comes into the play: The language, the text. How would the dance have worked if the singer had not given his voice to the dancer? So to the next question: How many people were actually on the stage in order to arouse this high-dramatic material to life? The two that could be seen – the instrumentalists apart – or only one in two manifestations? Is Monteverdi’s Lamento d’Arianna really only the musical centre and pivotal point, or more the egg which from the chicken – the true performance – slips? In addition: How deeply would the singing and lamenting of Arianna have moved us without the dance? One thing is certain: this was very much an enthralling evening, perhaps “THE” evening of the European Kirchenmusik Festival 2008 in the view of the extreme emotions aroused and displayed – so much so that the constant exploration of the music brought it to even greater heights. „Lasciate mi morire – Let me die” sings Ariadne, craving death in her sorrow and despair – exactly the material this performance is built around. Ariadne was sung by one the finest Countertenors of our time, Christopher Robson. A man in the role of a woman? Today perhaps rather rare, whereas in older times it was often the norm. How did he deal with this role? He made it a simple, moving and gripping journey. But not only this, while he offered much more than the usual Countertenor sound; not only beautifully and roundly polished but also malevolent, hard, cruel, full of despair, raw, tenoral, bursting with emotion, overwhelming the audience with an extraordinarily commanding physical control and body language.

Through him the emotional world of the Renaissance united with the early Baroque and the physical world of Butoh. In him woman and man also came together. Externally completely a Man, no longer a young man; internally completely Arianna, cruelly abandoned, who wants nothing more than to die, preparing to put an end to her misery. And with such directness, so that in no way did he ever seem androgynous, he not only brought his masculine being bodily into the public but also his radiance brought Arianna glowingly to life. Here Robson was completely the Man of the Baroque; so sensuous, so magnificent and full of joy in life, thus we can see one side of the Baroque – Monteverdi stands more than on the edge of it — also so hard, so close to dying and death and the ugliness that is the other side. Even so, despite all the colourful splendour, also Black and White – like the Butoh dancer Yvonne Pouget. Black-and-White is also the picture offered for apparent contrast, which is united in Butoh: Old Japanese dance traditions and elements of the Expressional Dance formed after the Second World War influence and generate Butoh dance form. The performance opens with Johannes Hieronymus Kapsberger’s “Toccata Prima”. Toccata comes from the Italian toccare, wounding blows, which the three musicians of the United Continuo Ensemble took very literally: Hard, violent, powerfully they played their instruments. On the raised stage the dancer with almost imperceptible movements, hidden behind a cat-like mask, bent, broken, loses her the mask, slowly goes off to the side, making the stage free for Arianna’s “Lasciate mi morire!“

Robson takes up the dance seamlessly, gliding slowly to the front, suffering and screaming mutely, then quietly forces the first sung notes into the room, lets the text flow, beseeches, cries out, walks, breathes, lives his Arianna. Again a change of actor; Pouget in a magnificent austere Renaissance dress floats into the playing area — in addition again Kapsberger, the “Tarantella di Sannicandro”. The white hands, the white face, the Renaissance dress, the volatile deep organ tones, the skillful ostinato of the Theorbo, the Cembalo: power which affects the small, but extremely intense movements of the dance, floating almost to the edge of insanity: Tarantella — St. Vitus’s Dance? The voice from off; is it a higher authority? Taking up the emotion of the Tarantella, the singing Arianna comes from the center aisle, wails her lament into the room, expression more important than pleasing sound, and in unison with voice and body. We hear water drops, dripping slowly as if in a cavern — from the musicians comes an Adagio from a Bach Viola da Gamba sonata, and two rhythmic worlds exist. Just like the flowing of the Bach the Arianna-Robson slides on her-his belly across the stage, flowing and crab-like.

Then, a fundamental change. A red dawn? Red light on the Christ figure in the quire, yellow light in the side aisles, a sung dance. And Robson becomes Arianna for a third time, pleading, suffers, sings as if it were his own feelings, putting Arianna’s despair into each note, preparing the “Corporalita” – here the union of body, spirit and soul as the first step of her cultivation: Pouget again black-and-white, Robson in a long black coat — a robe? — and with welder’s goggles, moving infinitely slowly apart: An unbearable tension prevails, pushing to breaking point, over the earthy tones with their machinelike rhythms filing more and more of the room, the dancer slowly but surely folds down to the floor. She strips off her black skin, creeps slowly forward, searching, rolls herself to the side in a kind of slow Break-dance as if being born again, while Robson peels off his robe, caressing himself lovingly. A mourning gown? A Skinning? Monteverdi’s “Si dolce e il tormento” is in this part of the performance like hearing “The Favourite of the Gods”: Singing and dancing with simplicity and modesty, the voice nearly childlike, refinement in tone and refinement in motion. In addition the self-confident posing dance, impressively graceful, a form of Narcissism. The Departure without title; a capella snatches of voice, the voice breaking, the road down the centre aisle, the dancer right at the back of the stage and in the quire, the Narcissus itself continuously rediscovering itself, rising above the pain and diving down again into its own world. It disappears behind the altar, the sound of the Viola da Gamba disappearing with it.

Darkness. And then inspired enthusiastic applause. “

About Christopher Robson:

(Countertenor) was born in 1953 in Scotland and is one of the best known singers in his fach with a repertoire ranging from early medieval Monodies up to today’s avant-garde compositions. He is especially admired for his skill as an actor and the commitment of his performances. He has performed all over the world, worked with many of the major orchestras (Berlin Philharmonic, London Philharmonic, OAE, Vienna Symphony, Concentus Musicus Wien, etc), conductors (Claudio Abbado, Sir Charles Mackerras, Mark Elder, Zubin Mehta, Ivor Bolton, etc) and directors (Richard Jones, Jonathan Miller, Nicholas Hytner, Willy Decker, Pierre Audi, etc), and made numerous recordings for radio, disc and Tv/Dvd. Since his debut with the English National Opera in 1981 with whom he appeared in many ground breaking productions, he has also sung for the Royal Opera Covent Garden, Opera North, Scottish Opera and Glyndebourne Festival Opera amongst others in the UK. He has appeared at many of the major European houses, as well as the Chicago Lyric Opera, Houston Grand Opera and New York City Opera in the USA, and the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow. Since 1994 he has been a regular guest with the Bavarian State Opera in Munich, where he was honoured in 1997 & 2002 with the Opern Festspiel Prize. In 2003 the Bavarian State bestowed on him the honoured title “Bayerische Kammersänger” in recognition of his work at the Bayerische Staatsoper and his contribution to Music & Culture in Munich and Bavaria.

< Top

Kommentarfunktion für diesen Artikel geschlossen.